Photometric Redshifts

September 12th, 2016 by Joe Bright

Image credit: Durham University (astro.dur.ac.uk).

1. Spectroscopic redshift

In the age of deep and wide-field transient surveys new transient sources are being discovered at an unprecidented rate. This rate is expected to increase again when next generation facilities, such as the Ruben Observatory, come online.

A key piece of information to have for every transient source is its redshift (or the redshift of its host galaxy), which can be used to calculate the distance to the object. Due to the expansion of the universe photons from distant objects are ‘stretched’ as they travel to us, causing their wavelength to increase (pushing them towards the red end of the spectrum, hence the term redshift). High resolution spectrographs, which measure the intensity of light of each wavelength, can then measure the wavelength offset of prominent emission or absorption features (casued by atomic or molecular transitions) as compared to those measured on Earth. The size of the offsetallows for a measurement of the redshift (and then a distance). A schematic demonstrating the effect of redshift on a spectrum is shown in Figure 1.

Due to the aformentioned number of new sources being discovered it has become unfeasible to obtain spectra for all targets of interest due to the time-on-source required to achieve a spectrum of sufficient quality.

2. Photometric redshift

While we are not in a position to obtain spectroscopic redshifts for all new transient sources (or their hosts), there is still hope when it comes to estimating their distances. When modern surveys scan they sky, they do so not just in one filter, but in many. A telescope filter determines the range of wavelengths that a telescope is sensitive to but, without a spectrograph, provides no information on how much light is at each wavelength (preventing redshift being measured in the traditional way). However, making measurements of an object’s brightness in a range of filters covering different wavelengths we obtain broad information on the shape of the spectrum (without the minute detail needed to measure the position of emission/absorption lines). Measuring the brightness of a target within a filter is known as photometry and we have photometric information of a huge population of galaxies in whih transients might occur.

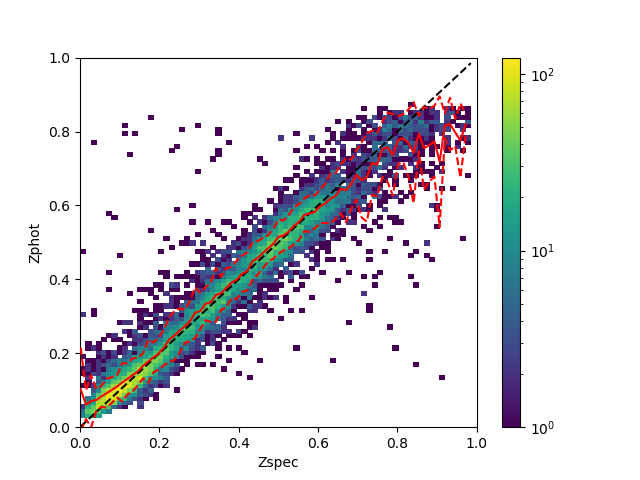

So, if the shape of the intrinsic spectrum of a host galaxy is somehow depentent on how far away it is, then we should be able to estimate the redshidt (or distance) with just photometric information. If a redshift is calculated like this, it is known as a photometric redshift.

3. Machine learning for redshift prediction

If we have a sample of galaxies with both spectroscoptic and photometric information we can use machine learning to predict the redshift of an object based off of its brightness in a range of filters.